Why the need for a different approach to building new communities

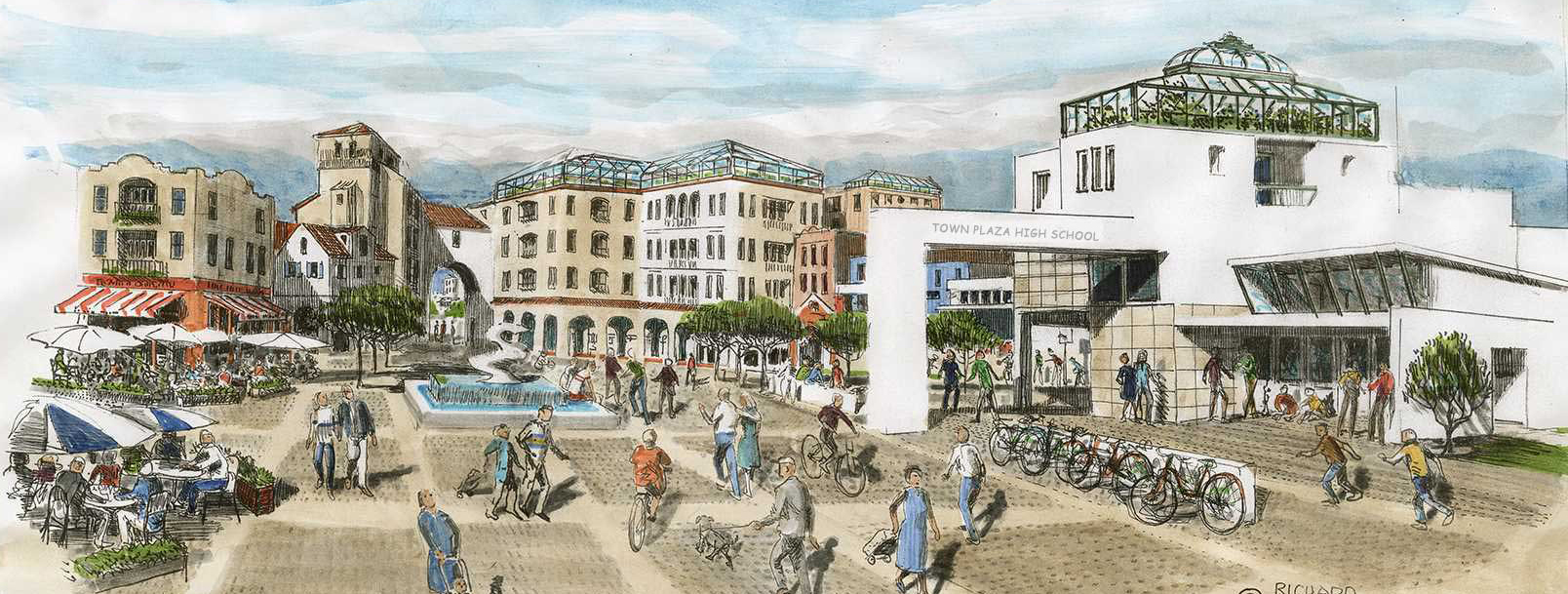

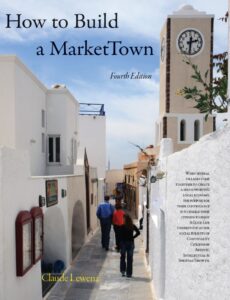

Travel to the old market towns of Europe and it becomes very clear: human connection. Narrow streets and lively squares drew people together. Shops, workshops, and homes intertwined so that daily life was shared, not isolated. A town wasn’t just a place to live; it was a fabric of relationships.

That connection was possible because it rested on a secure economic foundation: a largely self-supporting local economy. Wealth was created locally, and it circulated locally, and in doing so, it sheltered the community from the wild swings of distant markets.

Today, by contrast, many new developments prioritize cars over people, growth over belonging, and global flows of capital over local resilience. The result is fragile: loneliness, dependence, and places that people do not love. If we are to build communities that endure in the 21st century, we must recover what those old market towns knew instinctively: that human connection and a self-supporting economy are not luxuries—they are the foundation of a good life.

This is not nostalgia. It is based on the acknowledgement that what we are doing now is not working. Everywhere we look, systems are failing. Children are graduating illiterate. Workers can’t earn enough to afford a home. Loneliness is becoming an epidemic and our physical health is in decline because we don’t use our bodies as Nature designed us. Our solution for climate change is to spend $20 billion buying offshore carbon credits. It goes on and on. Yet when we look to timeless models – what a 1977 book called A Pattern Language, we find a wealth of solutions that cost less but return more.

We live in an age of soundbites and 280-character solutions. But a community is not built on slogans. It succeeds only when its economic foundation is secure, its design supports daily life, and its social fabric fosters connection. These elements cannot be explained in a tweet; they need the space of a full argument, because the details are what make the whole system work.

This site sets out the idea of the 21st-century MarketTown: a new approach to greenfield development that restores economic self-reliance, strengthens local ties, and avoids the design mistakes that leave people isolated and vulnerable.

Preparing for an AI/robotics economy.

Preparing for an AI/robotics economy. Policymakers talk about our ageing population — reports, reviews, and strategies — yet little changes. The problem is seen through the wrong lens: a car-based society where the default answer is segregation in retirement villages and nursing homes.

Policymakers talk about our ageing population — reports, reviews, and strategies — yet little changes. The problem is seen through the wrong lens: a car-based society where the default answer is segregation in retirement villages and nursing homes.

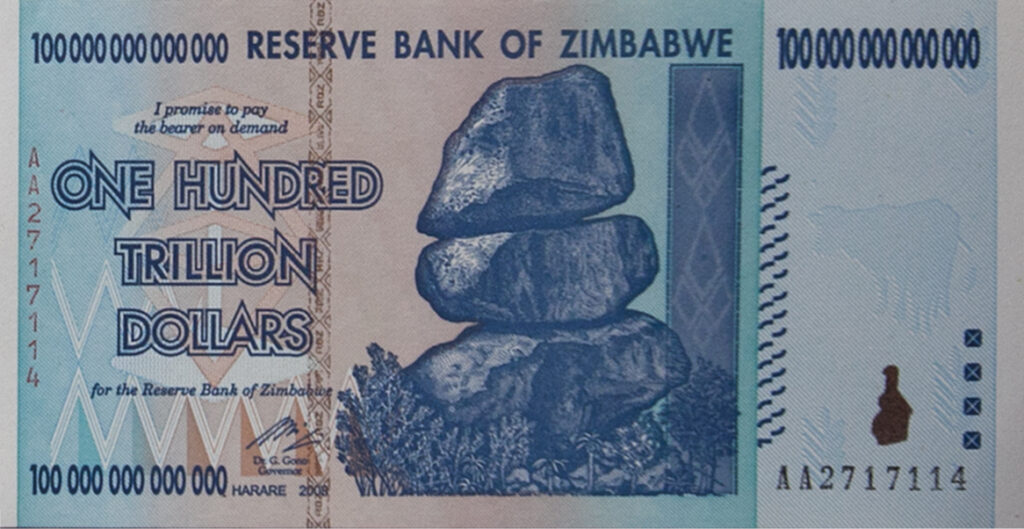

As the global economy becomes more interrelated, the risk of global meltdown increases. The best way to protect against this is to lower dependency on it. A local economy needs the global economy to thrive, but when, for whatever reason, it fails, a local economy has the basics covered.

As the global economy becomes more interrelated, the risk of global meltdown increases. The best way to protect against this is to lower dependency on it. A local economy needs the global economy to thrive, but when, for whatever reason, it fails, a local economy has the basics covered. Society’s decision makers were born in an analogue era where much of life was face-to-face: nonderivative reality. Younger generations grew up with an evolving derivative reality, where experience comes via digital transmission.

Society’s decision makers were born in an analogue era where much of life was face-to-face: nonderivative reality. Younger generations grew up with an evolving derivative reality, where experience comes via digital transmission. Many reasons — but nearly all trace back to misguided legislation: the RMA, the Building Act, and layers of regulation shaped by lobbying rather than good governance. Over 50% of development costs are the cost of permission.

Many reasons — but nearly all trace back to misguided legislation: the RMA, the Building Act, and layers of regulation shaped by lobbying rather than good governance. Over 50% of development costs are the cost of permission.

Children learn by watching adults. Isolate them in campuses, and they turn to the Internet for role models—then we wonder why they struggle as citizens.

Children learn by watching adults. Isolate them in campuses, and they turn to the Internet for role models—then we wonder why they struggle as citizens.

Too often, young people are isolated from the world they are about to inherit. Without guidance, work experience, or the chance to put down roots, they drift toward screens, temporary jobs, and distant housing—leaving them unprepared for adult life.

Too often, young people are isolated from the world they are about to inherit. Without guidance, work experience, or the chance to put down roots, they drift toward screens, temporary jobs, and distant housing—leaving them unprepared for adult life. In a MarketTown, that transition is built into the community. Apprenticeships, civic projects, and entry-level jobs connect teens to real work and responsibility. Affordable starter homes and mixed-use neighbourhoods let them live near where they learn and work.

In a MarketTown, that transition is built into the community. Apprenticeships, civic projects, and entry-level jobs connect teens to real work and responsibility. Affordable starter homes and mixed-use neighbourhoods let them live near where they learn and work.  For parents, nothing matters more than the safety of their children. But safety today is far different than the old days.

For parents, nothing matters more than the safety of their children. But safety today is far different than the old days.

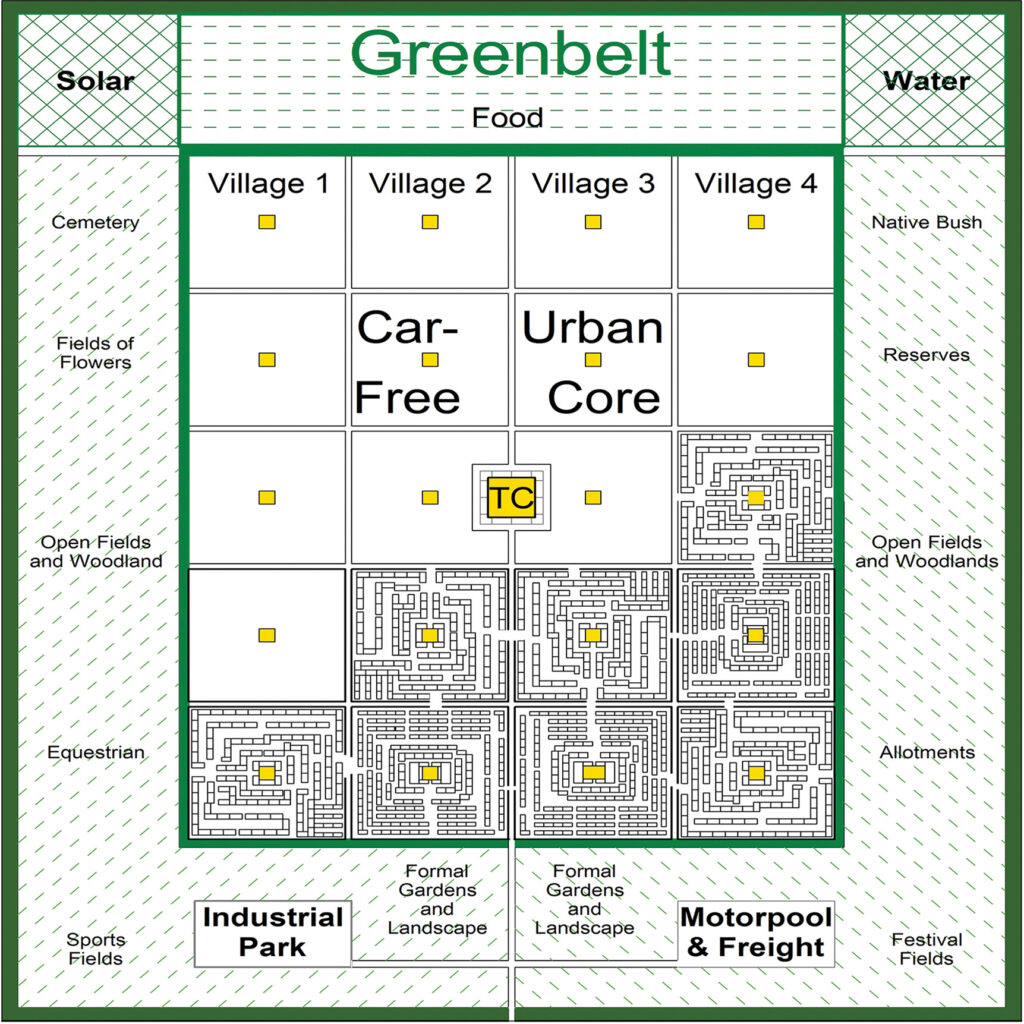

The result is a town alive with variety: different foods, festivals, and ways of life — distinct yet connected, each village enriching the whole.

The result is a town alive with variety: different foods, festivals, and ways of life — distinct yet connected, each village enriching the whole.

Land: 200 hectares of greenfield—not prime farmland, but land suited for settlement.

Land: 200 hectares of greenfield—not prime farmland, but land suited for settlement. Too often Green ideology results in greenwash, greenflop and greenwreck. Spending $20 billion tax dollars to buy overseas carbon credits is greenwaste. New Zealand makes up just 0.17% of global emissions. Why do we use Green to make life harder?

Too often Green ideology results in greenwash, greenflop and greenwreck. Spending $20 billion tax dollars to buy overseas carbon credits is greenwaste. New Zealand makes up just 0.17% of global emissions. Why do we use Green to make life harder?